Coincidences, Coincidences

Brahms Brahms Brahms!

I have an obsessive personality. It’s not great for watching Battlestar Galactica, but is a net positive. But, when I become fixated on something, it’s helpful to ask why my brain might be pointing me towards something. This week, a few obsessions became unwittingly intertwined. The locus: a hairpin.

Coincidence #1

I’m currently reading Christopher Berg’s Practicing Music by Design, a fascinating look at the intersections of the intuitions and practice strategies of great musical performers and the more recent discoveries around motor learning, psychology, and “peak performance.”

Berg makes much of the powerful and prescient pedagogy of pianist Theodor Leschetizky, as described by his pupil Malwine Brée. So, imagine my delight when my “random text about anything” colleague Mike Truesdell shared a video of a grandpupil of Leschetizky, Seymour Bernstein, discussing interpretive concerns in Chopin’s Prélude in E Minor Op. 28., No 4.

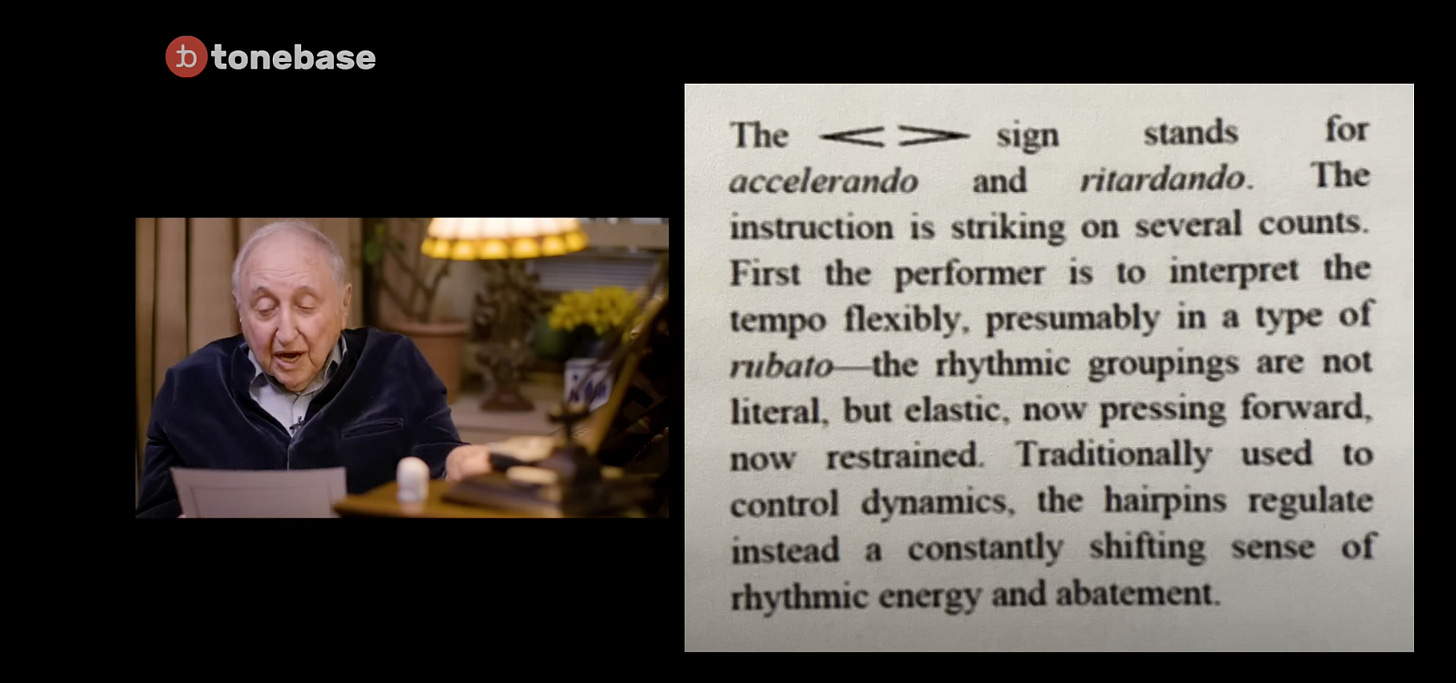

Amidst admiring Bernstein’s voluptuous jacket and being captivated by the ASMR sound of his card stock papers shifting on the music desk, I was taken Bernstein’s dalliance into hairpins in the music of Brahms.

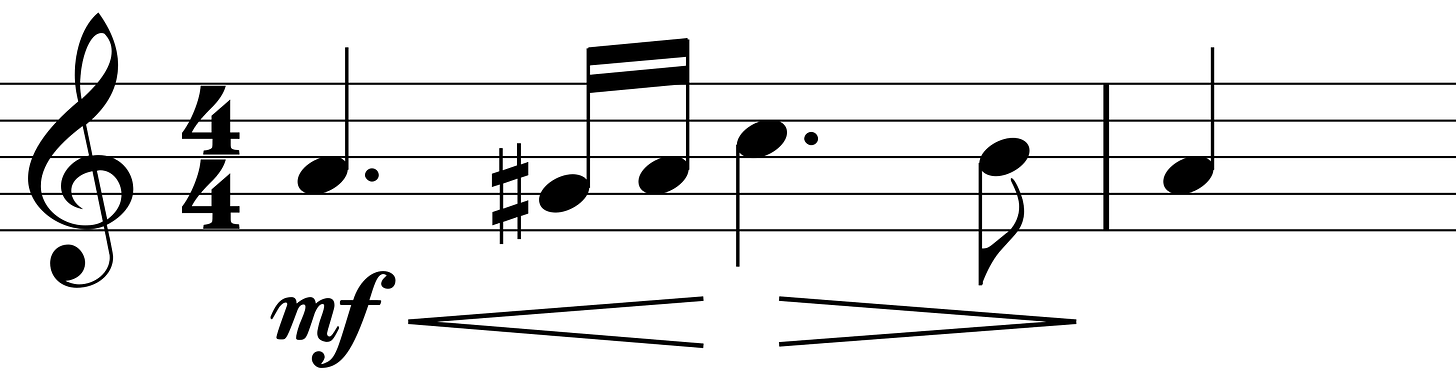

For those of us in contemporary music, we see

And interpret the symbols as denoting dynamic change from soft to loud and back.

Bernstein’s choice of words (”written in stone”) is odd, since his argument is that in the music of Brahms and his contemporaries, this musical marking denotes not dynamic level, but heightened expressivity.

If you are steeped in the music of the 19 century, you probably know this. If not, let’s examine:

Fanny Davies, influential 19th-century pianist and a student of Clara Schumann, reported from a rehearsal with Doktor B that “When Brahms came to the double hairpins, he played with extra warmth and affection, not only with tone, but with Rhythm also” (quoted in Cobbett's Cyclopedic Survey of Chamber music (London, 1929).

Interesting. Let’s get a second opinion. Fanny Mendelssohn:

Bernstein is right: “Wow. Is that explosive information.” (Although I might have mustered a little more enthusiasm.)

In his excellent article “The Brahmsian Hairpin,” David Hun-Su Kim goes further, arguing that

“hairpin notation has accordingly provoked commentary from a diverse array of musicians…all of whom agree that hairpins are not dynamic markings, but rather connotative expressive indications that are frequently associated with rhythmic inflection.” To Brahms, hairpin markings were not “well-defined prescriptive sonic commands but rather… descriptive markings connoting expressive meanings.”

My world is shattered.

Coincidence #2

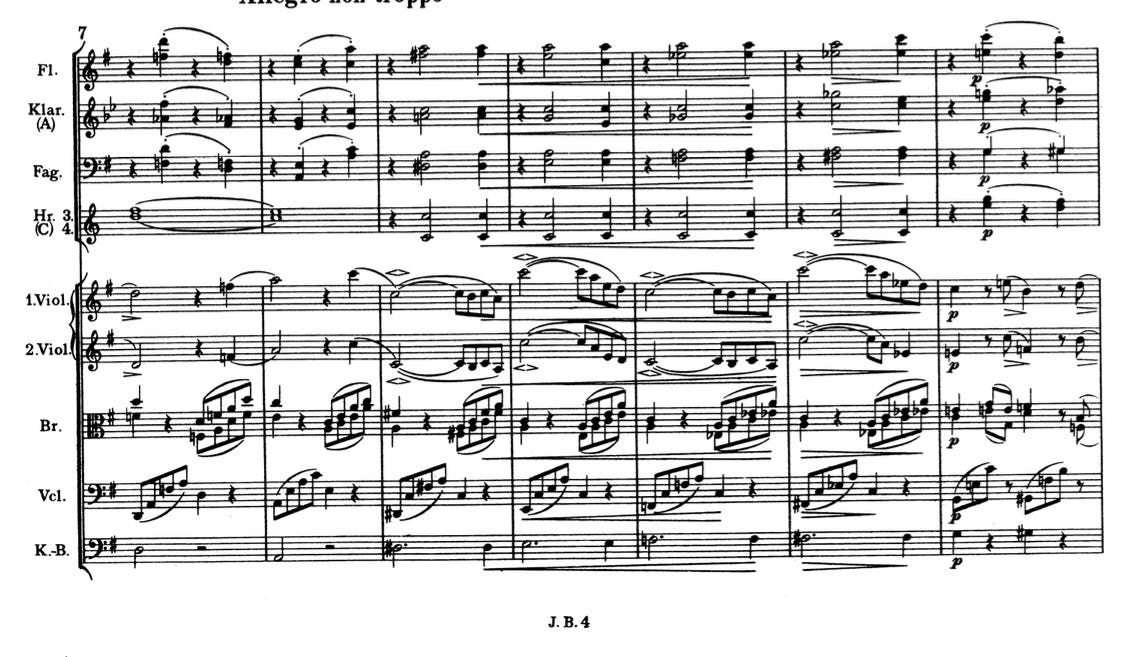

I have been obsessed with Brahms’s 4th Symphony for the past few weeks, and it just so happens that one of my favorite moments (which occurs around :17 into this phenomenal recording) is full of hairpins.

Here we see 3 species of hairpins.

In all systems, we see a what Kim calls an “accelerando” hairpin, which typically implies a localized speeding up.

After, we see what Kim might call a “lingering-closing” hairpin, which might indicate slowing at an expressive peak, or otherwise closing a phrase off.

The tiny <> over the violin parts (sometimes called messa di voce) implies “do something here,” which might mean a lengthening or slowing of a beat, or the use of vibrato to create a new color.

So, the hairpin is not denoting something, but connoting something. This is not new information. So, why did this tickle me so much?

“You Should Know”

First, I love an expressive marking that indicates the presence of something expressive, but does not give a clear sense of what to do. I have a friend whose mantra “you should know” sounds awful Brahmsian right now.

Similarly, this Brahms epoophany (small epiphany) got me thinking about other written expressions whose connotation might have been obfuscated since the time of its usage. When has the meaning of something we think of as immutable so changed that we need help to dislodge our contemporary preconceptions?

Tom Toms in the works of John Cage?

In a previous newsletter I mentioned a lecture in which forte-pianist Malcolm Bilson interrogates durations within 19th century repertoire. I’m convinced, particularly around affect.

The Text is Not Enough

At the same time, thinking on Brahmsian hairpins reinforced a notion rattling around my head recently, that the “text” of an art work is often not sufficient to interpret that work with profundity and flexibility. We as performers need to know what makes this text unusual, noteworthy, innovative, challenging. Only then can we bring it to life in a different context than that of its creation. These hairpins are performance practice. At the same time, they are signal that if we want art to live renewed in perpetuity, we need to have some sense of how it might have felt at the time of its creation in relation to all the other NON-hairpin moments

Just like treatises, a topic of a recent post, oral history forms a key part of our interpretive energies. How someone said or wrote to perform a piece of music “correctly” is fallible to the extreme. At the same time, however, what performers, composers, and audiences say about what constitutes a great (or terrible) performance can be a powerful addition to our knowledge, provide that we keep in mind our primary goal of connecting with communities around our performances and calibrate or convert accordingly.

What’s nice here is that Brahms is saying to do something, but the expressive thing could be what’s effective in 2023, not 1884.

Coincidence #3: The Specificity of Impressionism

Why did this hairpin spiral impact me so much? Let’s look at some art.

While visiting the Philadelphia Museum of Art with a friend recently, I was struck by a few Monet’s I hadn’t seen before.

In the autumn painting, light radiates from the horizon, illuminating a space in between the trees in the water. The ground is vibrant, alive with a pinkish hue. In the railroad bridge, the clouds laminate a particular luminosity, reflecting the bridge onto the water. In person, these are awe inspiring, hand squeezing works.

Why is it the light in this supposedly “impressionist” painting more realistic, powerful, and clairvoyant than in so many works of “realism?”

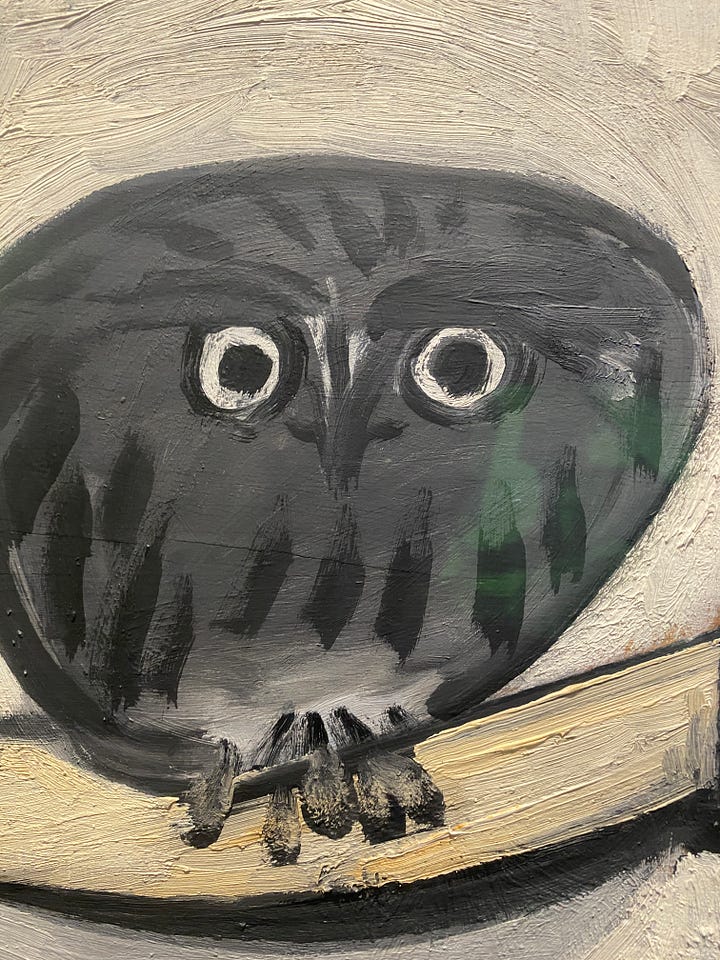

How about this Matisse-ian plant? Or Picasso’s Owl? Neither is ready to be included in a new edition of Audubon’s Birds of America, but they are rich and expressive, indicating “more” much more effectively than a photo.

They are hairpins!

Brahms doesn’t tell us what to do. He tells us how we should feel about it. He (like Monet and Matisse) hints at the inner life of his work, a subjective feeling that can more easily be transported across space and time than an extremely detailed description of what to do. It’s more specific and powerful and dynamic.

Conclusion: emotion is challenging to denote with durability, but not so hard to connote with specificity.

I’m hoping to split my writing into a longer post and a shorter post each week, so stay tuned for some less tangled missives.

Other Ideas

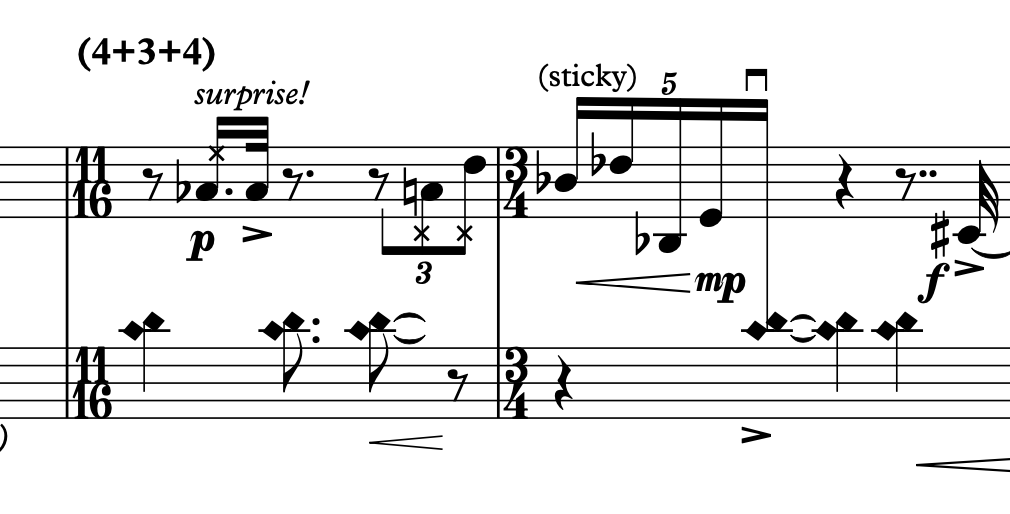

For another example of “something is happening here,” I love this marking in Tonia Ko’s excellent marimba solo Blue Skin of the Sea. In this passage, the marimbist is scraping the instrument with plastic mallets:

Accents and hairpins notwithstanding (BTW, accents are just short hairpins…), I love Tonia’s coded language. “Surprise!” indicates to me that this passage is different in some way from a previous iteration of similar material. In fact, the articulations are inverted. But, Tonia does’t say what to DO with that information. In the next measure “(sticky)” is a clear description of the articulation needed, but the use of parenthesis indicates “you should know,” a tacit reinforcement of something the an astute performer would do already

Here’s the spot in question