Socrates thought the unexamined life was not worth living. But what about the over-examined life? We are about to find out…

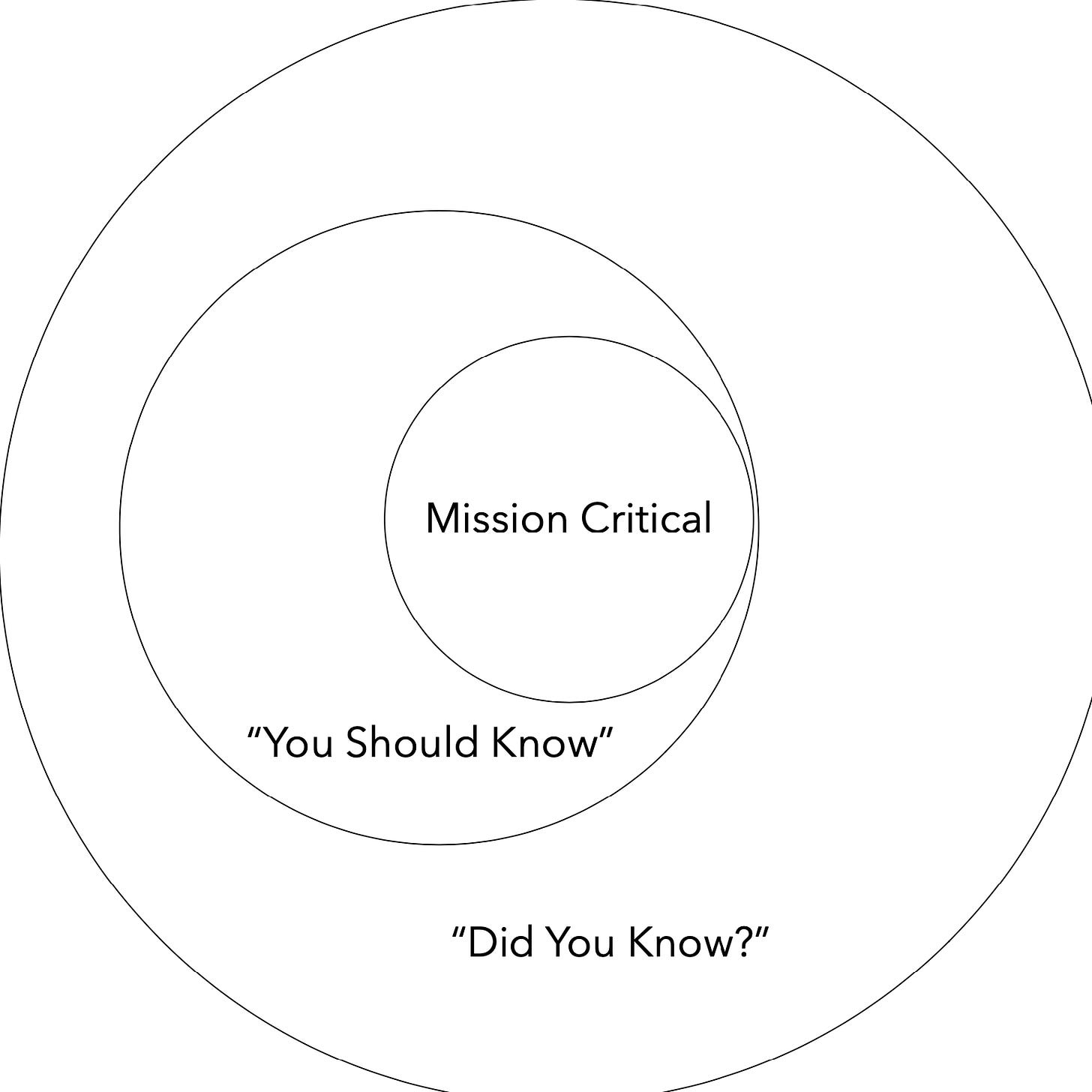

Last time I laid out some thoughts on how I would approach the teaching of fluid and flexible musicians. I argued that it makes sense to approach subject matter expertise from the outside in, much the way we market ice cream sizes:

Gotta have It (12oz): books that speak across domains, books on learning, history, cultural studies, psychology. Least likely to change, but most dynamic in thought. “Senior liberal arts college students elective” zone. This circle is the most important because it subsumes the others

Love It (8oz): writings on music, texts which speak to the historical periods in which the musician wants to inhabit, or the history which informs the present. Texts on professional development. Susceptible to editing and moderately squirmy in thought, but worthwhile.

Like it (5oz): domain-specific information about percussion. Most fungible, but the most susceptible to dogma. Must read, but also must critique.

As I mentioned last time, discipline-specific texts often take primacy in graduate comprehensive exams. Yes, percussionists need to know about percussion. But doesn’t learning about music help one contextualize their percussive knowledge?

Despite the fact that this is a “summer” reading list in name only, I’m curious whether studying to be a powerful musician can make one a better human(ist) along the way. With that in mind, let’s move from the “did you know” to the “you should know” circles.

Kind of Big Thoughts

These texts toe the line between helping us learn more broadly, and taking on discipline specific information.

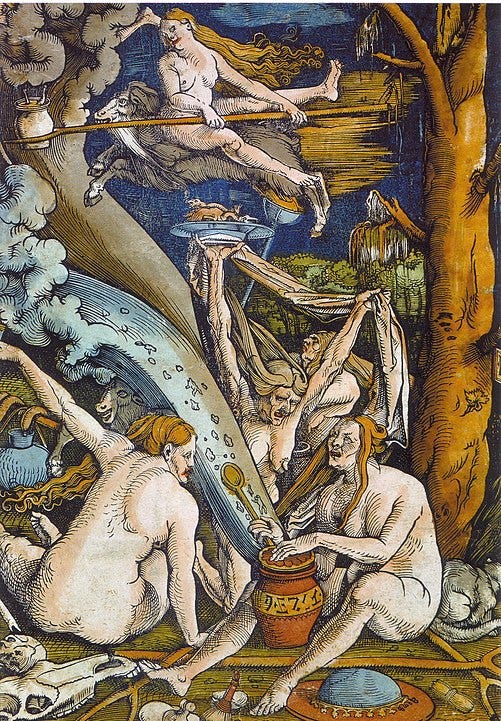

Ginzburg, Carlo. The Night Battles.

In the 16th and 17th century, a group of Friulian farmers left their earthly bodies, and, armed with fennel fronds, fought off witches and demons intent on destroying their crops. At least, they said they did. The Night Battles examines the inquisitors’ trial of a pair of these benandanti, juxtaposing the farmers’ claims that they were protecting the earth with the inquisitors’ increasing beliefs that the benandanti’s work was itself a kind of heretic sorcery.

What can a book about 16th and 17th century Roman Inquisition trials of witch hunters tell us about music? Much of our work as musicians centers on interpreting musical texts which, as we’ve noted, are inherently incomplete, absent critical information. In these witch trials, missing from the records are the questions the inquisitors asked, leaving us readers to determine the nature of the questioning from the respondents’ answers. This practice is wonderful preparation for the typically one-sided conversations we have with musical scores. At the same time, music’s meaning is locally contextualized, meaning that it’s meaning changes with time. Ginzburg shows with almost laughable specificity how the same story repeated in the same fashion can shift from miraculous rescue to satanic ritual.

Grout, Donald. History of Western Music

I had a teacher once told me that if I could discuss any word written in bold in this book, I would be set as a musicologist. Spoiler, I wasn’t. Reading this book is akin to taking a one semester history of all civilizations, proving to me that sometimes one can be too general! Should a percussionist read the Grout in 2023? Perhaps not, but investigating whether this book has a “vibrant narrative” and whether it explains “what’s important, where it fits, and why it matters” is a “fun” break from snare drumming.

Does the number of editions speak to its longevity, or the obfuscating, difficult to parse narrative? I love history, and my copy is covered with a lot of drool. Actually, maybe we should ditch this one.

Capturing Sound investigates The Phonograph Effect, the way in which recorded sound changed not only how we listen to music, but how we create it. Recorded music is tangible, invisible, portable, and repeatable. It can transcend temporal and locational specificity, is infinitely repeatable. Millions can hear the exact same recording, and the impact of this Benjaminian mechanical reproduction cannot be overstated. From articulating a theory of increasing string vibrato as a matter of exigency, to exploring the complex world of sampling within DJ culture, Katz highlights how recordings have fundamentally altered our perception of what music can and should be.

In class, Katz would intone that “a recording is a recording and a concert is a concert, and never the twain shall meet,” and this dichotomy has been on my mind since. Capturing Sound has always been a great exemplar for me of how to write wittingly and engagingly about the technical and aesthetic side of music making. In particular, his assignments around comparing recordings of the same piece attuned my ears, sharpened my vocabulary, and enabled me to speak about what exactly constitutes an interpretation. Plus, TAing for Katz’s History of Rock and Roll class was a life highlight…

Poultney, David. Studying Music History

A secret weapon for music students. Poultney posits a parametric approach to the study of music history: analyzing various broad time periods through musicians attention to rhythm, form, melody, color, etc. For those studying for exams, Poultney’s clarity, organization, and surprisingly difficult sample questions are a no-brainer. I remember copying out the charts, and hoping I would never again think of melismatic tremble lines in the Ars Nova.

Dudley, Shannon. Carnival Music in Trinidad

Dudley gives an aesthetic history of calypso, steelband, soca, and other genres active in and around Trinidad. These musics and the instruments that play them are powerfully intertwined with politics and history, and these tensions emerge each year during Carnival. I love how Dudley shows how music can be a tool to teach people how to be members of a community, a carrier of history, a political weapon, and a vehicle for shared identity. At the same time, this music highlights the importance of diasporic music in the Western hemisphere. There are many texts that take on these themes—my argument is that it’s incumbent on us to engage with how music creates and transmits “culture.”

Those of us in music might accept Ross’s oeuvre as selbstverständlich at this point, but I’d point anyone interested in how to write compellingly about music towards The Rest is Noise. Ross embodies the “disembodied eyeball” approach of the New Yorker’s taste-makers—lucid, cogent, dispassionate depictions not only of music, but of musical events. This is a history of how details and epiphanies in a particularly volatile and uncertain moment, a depiction of how music is both ensconced cultural and moves culture forward. While a little Thomas Mann focused for my own taste, a little obsession never hurt anybody. This is a depiction of the romanticism against which the Darmstadt composers so vociferously rebelled, and as such has a tremendous impact on percussion repertoire. A great read before diving into the nuts and bolts of pataflaflas (this video, by the way, has a LOT to look at in the background, from harshly lit ionian (??) columns to some killer product placement).

ANECDOTE ALERT: I remember Mark Katz introducing Ross for a lecture in Peabody’s musicology colloquium about the role of music in Hitler and Stalin’s regimes. Ross had a tape (!!) of musical examples, and Katz remarked that the lecture itself was a “phonograph effect,” because both Ross and the audience were beholden to the timing and ordering of the recording.

Developing One’s Profession, Like It or Love It

The role of the doctorate in professional and scholarly development has changed fundamentally in the past 10-15 years. In music, academic positions are increasingly rare. (So are positions in orchestras and as concerto soloists, but that’s a topic for someone else’s newsletter).

Within this milieu, I think of the DMA as potentially taking two paths.

The doctorate still has value as a credential. For those interested in scholarship, those obsessed with a topic, interested in professional demarcation of some kind, a DMA or PhD is immensely valuable.

In an artistic environment where there have never been as many skillful practitioners, percussionists interested in a performance career could think of a DMA as an opportunity to develop a professional portfolio, network, and skillset while receiving both some measure of institutional support and mentorship.

That said, overall DMA programs in general can take broader and more action-oriented notions of professional development. So, some thoughts from the murky field of “professional development”

Forshee, Zane, Christina Manceor and Robin McGinness. The Path to Funding

I can’t be more inspired by the intrepid work of Zane and his team at Peabody: their Breakthrough curriculum is a terrific example of how to integrate “careers” into curricula, and this text is emblematic, covering ideas on generating powerful ideas, engaging communities around those ideas, and finding sustainable funding to create transformative art. It’s tool/skill based, and it’s free!

Burnett, Bill. Designing Your Life

This book was recommended to me by a dear friend, and I’ve found it hilariously catharsis-inducing among my students. Is it written in the style of a self-help book gone amok? Yes. Are the graphics and charts cringe-inducing? Yes. Has it been catharsis-inducing among my students? Also yes.

So often, music school degree pathways negate (actively and/or passively) the notion that creatives have the joy of crafting an artistry and profession that is uniquely their own. Burnett focuses on career discovery, “sampling periods,” dreamed through mind maps, actioned through informational interviews and supported by Design Thinking. Designing Your Life has helped my students conceptualize blended careers (ie not just snare drum (not that there’s anything wrong with that!)) while encouraging them to experiment. It helps answer the WHY and WHAT so necessary in the study of music.

Myles Beeching, Angela. Beyond Talent

A classic, devoted to those pesky professional practices outside the practice palladium. A good resource for crafting powerful materials: CVs (if there are such things…) cover letters, press kits. A great resource for conceptualizing a career in the arts.

Kelsky, Karen. The Professor is In

Wonderfully practical text on taking academic skills into the professional world, covering everything from applying for, receiving, negotiating for, and leaving academic jobs. While the book is ostensively about the planning required to transform a PhD into tenure, I appreciate her realism about academia and the pivotable soft skills humanities scholars develop is poignant and practical.

Baumgardner, Astrid. Creative Success Now

After working with Astrid in and beyond school, I was excited to read her effusive book on how creative abilities can empower professional pathways. In particular, I appreciate her focus on creative skills as professional practices.

I remember the composer Alejandro Viñao talking about Xenakis’ percussion works as falling into two camps: ‘paperback’ and ‘hardcover.’ These are ‘paperbacks’ in physical presentation and spirit, but sometimes one needs that immediacy. Plus, many of these authors have thriving blogs and newsletters, which are a great way to get in touch with more plastic and liquid thoughts than those immortalized in published print.

“Like It:” Books about Percussion

I believe that learning about one’s instrument is facilitated by learning about the world more generally, and about the schemes and tropes of music-making more specifically. The larger circles of context swirling around music have to be a part of what we do in the practice room, as they inform what we do, how we do it, and why. With all that in mind, here are some percussion-specific books. I’m leaving out much with regard to repertoire study and instrumental technique, but I hope to share on those in the future.

Schick, Steven. The Percussionist's Art: Same Bed, Different Dreams

A dazzling percussionist whose memory and virtuosity changed our field, Schick is an interpreter, and he is a major figure in what I would call “third generation” percussion performance: positing percussion as an instrument capable not only of execution, but of poetry. his performances are stuff of legend: famously memorized, famously instrument agnostic (he doesn’t care what instrument he plays), famously “so impressive it’s not impressive.” Underlying all is a perceptive and critical mind, and The Percussionist’s Art is an essential guide our instrument through case studies around memory, collaboration, theatricality, and more. In addition, his depiction of percussion history through generations of thought is powerful.

Probably the only book about percussion I would recommend to my father (and I did!).

Beck, John H. Encyclopedia of Percussion

Aiming for encyclopedic knowledge of percussion. Encyclopedia is in the title, folks! Purporting to cover both percussion and concussive instruments, I like that Beck offers not only an alphabetized listing of instruments and discourse around them, but a number of articles covering various percussion topics. Cover art is underwhelming, but we can look beyond that.

Blades, James. Percussion Instruments and Their History.

Classic percussion text covering the history of percussion instruments from Ancient Greece to the present (well, in 1992). Blades was a close collaborator of Benjamin Britten, so the book skews British. I tend to read against the Blades, which omits or essentializes many non-Western cultures, and includes many many many problematic depictions of "primitive musicians.” Through the valiant efforts of Norman Weinberg, the Blades is once again available, in (gasp) digital format!

Hartenberger, Russell (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Percussion

Assembled by famed percussionist Russell Hartenberger, this companion includes chapters from some of our field’s luminaries on a few salient themes of percussion study, from orchestral percussion to instrumental development to composition. In particular, I appreciated the chapters on performance practice, where specificity of thought.

Udow, Michael. Percussion Pedagogy

A massive tome from percussion pedagogy legend Michael Udow, who, from his perch at the University of Michigan, transformed how many of us think about playing an instrument which is really not an instrument at all. You know offers a comprehensive and empathetic approach to the teaching of percussion, of course, but more broadly the teaching of musicianship through percussion. Love the accompanying videos, which are time capsule-worthy.

Siwe, Thomas. Artful Noise: Percussion Literature in the 20th Century

Siwe is oft appreciated in the percussion world by virtue of both his textbook for the teaching of percussion methods, typically a required course in Music Education degrees and his massive Percussion Ensemble and Solo Literature compendium. Who better to tie together the disparate threads of percussion history? In Artful Noise, Siwe lays out the phases of the development of notated percussion music in the 20th century, prioritizing style and themes over chronology. The book is compact, and maps pretty well on to a semester-long percussion literature course. Just saying!

Happy reading!!