Amidst the end of semester chaos, I found space to enjoy Ken Burn’s new Leonardo Da Vinci documentary (great music Caroline!!!), and was inspired to revisit Leonardo’s notebooks, which are reproduced in full 1990s splendor here. For those interested, here’s a facsimile-maker’s account of the strange journey these documents have taken, and a google arts and culture write up on one of the codices.

A self-described “disciple of experience,” Leonardo’s notes-to-self are masterful analyses of the world around him. He summarizes some new piece of information, articulates it in his own words (often with images), and makes connections, analogizing between disciplines to articulate structural similarities with the goal of increasing his aptitude for understanding the world around him. Leonardo is a master at reflection.

(BTW, Leonardo’s tendency to leave commissions unfinished and rather go deep into “birds” or “how does water work?” resonates)

Reflection involves articulating the specifics of an experience, making thematic observations, and connecting these experiences to broader contexts. It’s a central practice in wiring and rewiring our nervous systems, memorizing and recalling information: to growing intellectually. In fact, one might argue that Learning = Experience + Reflection.

Here, habitual journal-writer Doogie Howser uses reflection to trigger an epiphany.

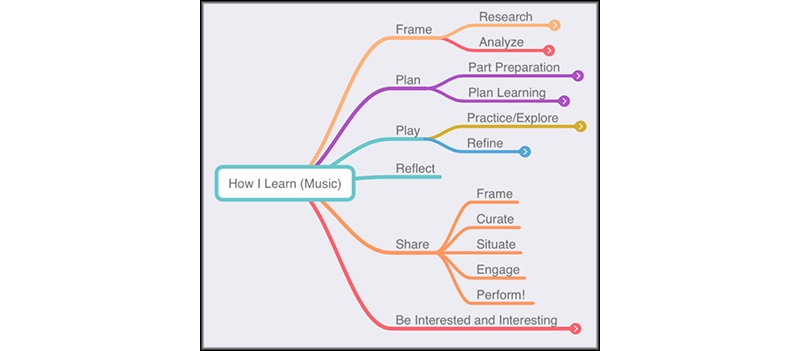

A few years ago, I wrote a “reflection on reflection,” where I outlined how lived experiences can inform future practices. In the intervening time, I’ve filled in the gaps, thinking about how learning music is a dynamic framework in which reflection is a central activity.

I dove into the ever increasing body of research and writing-about-research on cognitive neurology, which has demonstrated even more clearly the benefits of reflection.

Benefits

In The Musician’s Mind, a quick spin through some of the research into neuroplasticity, Lynne Helding breaks the learning process down into three broad steps: attention, learning, and memory. Throughout, our brains encode, consolidate, store, retrieve, and reconsolidate information.

Reflecting, ideally temporally close to the experience, is a critical to the encoding and consolidation phases of our learning, moving information from short-term to long-term memory, from soft and slippery (the wifi password at that AirBNB) to hard (your phone number).

Reflection also enables more effective storage and retrieval of encoded knowledge, facilitating neurogenesis and neuroplasticity—the two processes through which our brains learn and deploy new skills—by offering desirable difficulties and cognitive interference. Thus, thinking about playing percussion helps generate strong mental models and secures your memories visually, physically, and aurally. Great for combating stage fright!

Finally, reflection helps us reconsolidate information we’ve learned while articulating which learning strategies have worked.

Here are 2 use cases that are front of mind in recent weeks. Perhaps they are of use to non-musicians as well?

1. Metacognitive Exercises: Reflection for Skill-Building and Refinement

But how do you develop the skills of reflection? By thinking about thinking: metacognition. (I haven’t dared to think what thinking about thinking about thinking would be…)

Just as important as the content students learn in a class is the process by which they learn it. Metacognition describes an awareness of this process: the ways we absorb, assimilate, and convey information and participate in knowledge production. Johns Hopkins’ excellent research on the subject argues that the act of reflection—or thinking about thinking—helps students “assess and adapt their facility with the knowledge and skills of a discipline,” making their thinking explicit, and to “transfer their learning to new contexts.” Mini Leonardi!

Here are some sample metacognitive questions that we used in our ASU Percussion Group, with the goal of structuring the development of reflective skills:

How did you envision, expect, or intend the performance to go? Did the performance go as you intended?

How much time did you spend:

Listening to recordings of repertoire? Studying the score? Marking your part with cues and other logistical information? Practicing your individual part? etc etc

Based on the information above, what will you do differently in preparing for the next performance? For instance, will you spend more time practicing? More time studying? Less time rehearsing? What questions would you ask the instructor? Be specific.

What advice would you have for a percussionist joining this ensemble next semester?

Long-Term Epiphanies

These metacognitive exercises can be unfurled over longer time periods. Our students at ASU have all sorts of amazing musical experiences. Some of these take the form of slow, hard earned epiphanies. Others, though, are rapid fire “epoofanies” (a tiny epiphany): a comment in a percussion group coaching, the way a guest artist inflects a melodic line, a composer’s choice of adjective, or the sudden burst of adrenaline from that first perfect four stroke ruff. All in one day! How do we continue to grow when the growing experiences seem to come too quickly to process in the moment? Reflection over the course of a busy semester, perhaps facilitated by metacognitive exercises, and perhaps undertaken (gasp) alone, can help experiences become memories, and help those memories become consolidated and reconsolidated into valuable expertise, without needing to relive the pain of those four stroke ruffs.

2. Distillation: Reflection for Efficient Learning

I taped almost every lesson I took during my undergraduate degree (“nerd!”). Even though I took copious (and, it turns out, illegible) notes during lessons, my written summaries of lesson recordings—typically made the same day or one day after—were more coherent and cogent. The research has supported these conclusions, showing that learning and mastery (which include neurogenesis and neuroplasticity) begin with refined summary and deliberate mental organization of lived experiences. This process fosters thinking in analogies, which empower structural-level analysis, which allows us to learn new material more effectively, and on and on.

Design Thinking

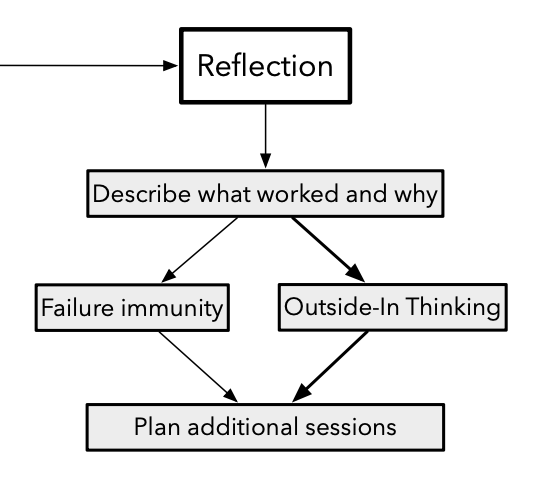

I think of reflection as the long-term form of Design Thinking. When crafting new interpretations or learning new repertoire, prototyping solutions, failing fast, and iterating new ideas, taking some time to create positive friction by slowing down to see what’s working and what’s not is essential.

So what are my reflections on the semester of creative projects? That will have to wait for next time. I’ll discuss how I leverage AI in curriculum development, experimented with memory, and checklisted our work.

Things I’m Liking Right Now

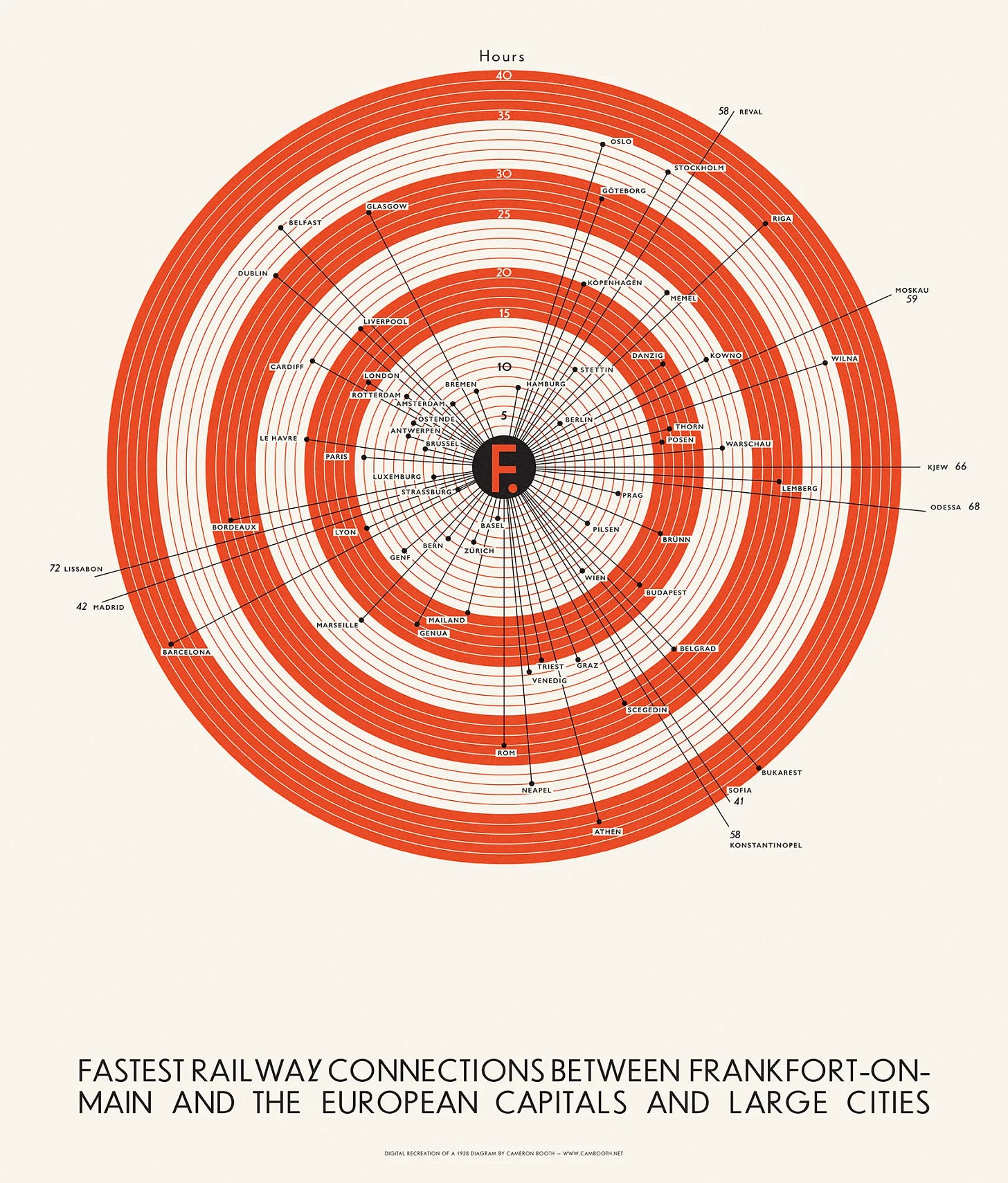

Just one thing. This amazing transit map. Just wow. #christmasgift